AN EXAMPLE: The soon-to-be-expanding Bear Family’s control system

(See the bottom of this post for the sample strategy referenced here.)

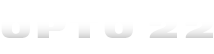

For those not sure about the what/why/when of pointers, let me give a hypothetical example. Suppose Goldilocks is the friendly neighborhood controls engineer, and she likes to make sure Mr. and Mrs. Bear always have porridge that’s neither too hot nor too cold. She might write a control flowchart that looks like this:

This is all well and good until one day the Bears announce they’re expanding, and will need a bigger porridge monitor/control system. They ask Goldilocks how difficult it would be to add another heater, fan, and temperature probe to the system.

Because she’s a smart controls engineer, and knows that most bear litters yield two or three or even as many as six baby bears (according to www.bear.org, anyway), she figures she better make some changes to this logic so it’s easy to expand in the future, since she and the Bears might be especially busy once that litter arrives.

THE BASIC IDEA:

Rather than just doing a copy/paste like she did from Mama’s logic when she went to create Papa’s logic, she considers using tables and maybe even pointers to make her logic more generic, and easy to expand.

The Setup / Monitor Part:

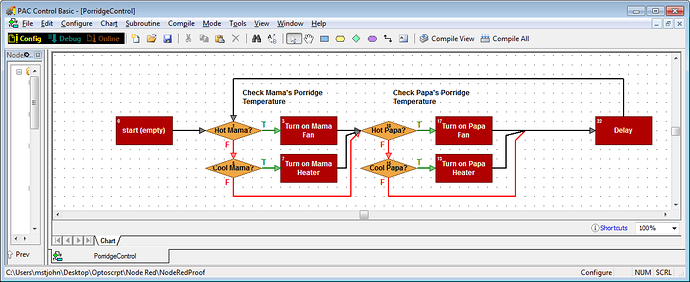

She wants to just have those two conditions to check, which she’ll check for this bear, then the next bear, then down the line until the end and back to the first bear. Sounds like she’ll need a list (or lists) of bear attributes to ponder so the final flowchart might look more like this:

That sounds simple enough (notice Goldilocks likes to start with this “high-level design” where she’s got her overall logic all laid out). Now she’ll figure out what to put in those blocks and work backwards from there.

She might even want to make some upgrades for the future, in case Mama Bear decides later she wants to adjust what “too hot” or “too cold” means on a bear-by-bear basis, perhaps from her Smartphone via groov!

Looping through Bears

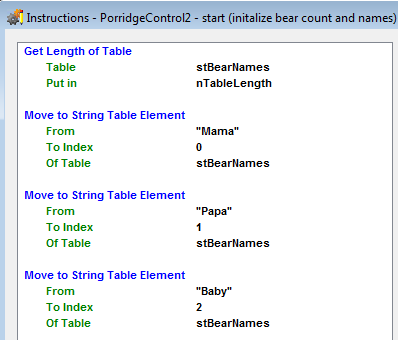

INTERNALLY, we’ll refer to each bear by a number or index, starting with Mama Bear as 0 (since that’s where computers and PAC Control tables start counting), for a total of MAX_TOTAL_BEARS (hoping 10 will be enough for now). This MAX_TOTAL_BEARS variable will be used in the new Condition block, when we’re deciding if we’ve finished with all the bears and it’s time to loop back around.)

But for our EXTERNAL users, like Mama Bear with her smart phone, we’ll want to store more human-readable labels for each. So let’s create and load that table, for starters:

Now let’s look at the new logic we added, and how we’ll keep track of where we are in the bear line-up. First we’ll increment the nCurrentBearNumber.

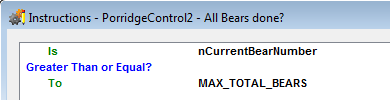

Then, here in this condition block:

[/B]check if we’re “done” which would be true if:

If so, we’ll set nCurrentBearNumber back to 0.

Now, here’s where it starts to get a little trickier, and we might want a pointer or pointer table, kind of like we use in this HIGHLY RECOMMENDED BY PRODUCT SUPPORT chart (which re-enables/connects your I/O Units if/when they get disconnected from your controller).

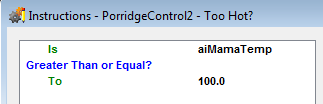

How do we change that temperature logic for “Too Hot?’ and “Too Cold?” to use the bear number instead of my current aiMamaTemp and 100.0 Literal?

We can use a float table for each set of values, one for “too hot” and one for “too cold.” I’ll call them: ftTooHotTemperatures and ftTooColdTemperatures. But what about that analog input?

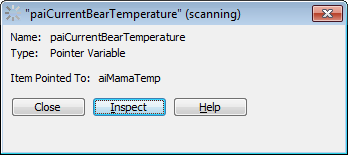

That’s where it would be handy to have a table of temperature inputs, and a pointer to the current bear porridge temperature. That way, our “Too Hot?” condition block becomes:

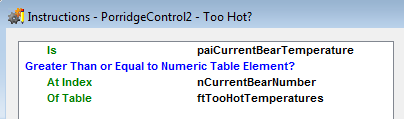

The “Too Cold?” condition block would be very similar:

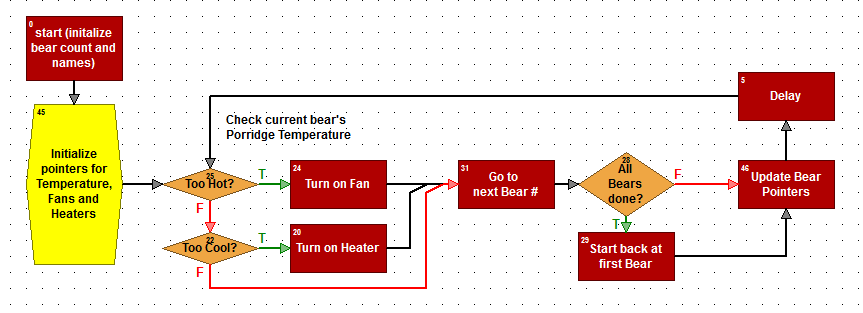

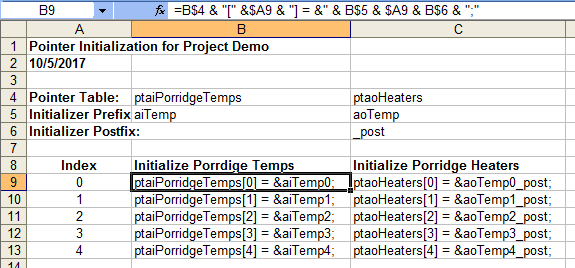

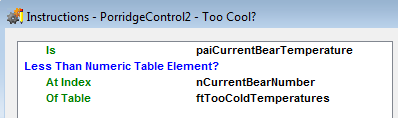

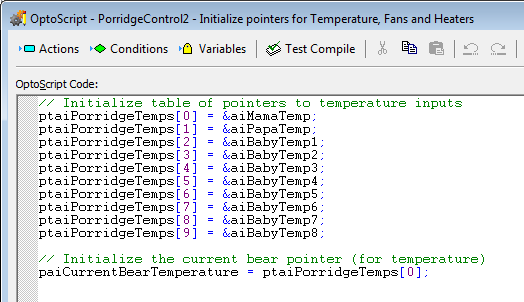

At the beginning of the flowchart, initializing that table of temperatures and the pointer to the current temperature looks like this:

Or in OptoScript:

Note: for that last “initialize the current bear” assignment/command, I could’ve just assigned the pointer: paiCurrentBearTemperature to aiMamaTemp, but initializing it from the table is more generic and easier to maintain. If someone ever moves Mama Bear out of the 0 slot, our loop will still start with bear 0.

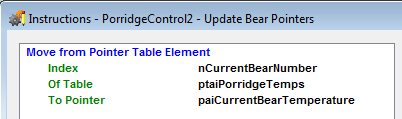

To move that temperature pointer to the next one in the list shown above, we’ll just use a command like this just before we do our delay and loop back around to the next bear:

The Control Part:

So that was the monitor part (where we went from looking at just the aiMamaTemp and aiPapaTemp to a whole list of analog inputs).

For the control part, we currently have 2 sets of two digital outputs (one for the fan and one for the heater). The idea is the same for those, I’ll just load up 2 more tables—one with a list of fan switches and one with a list of heater switches.

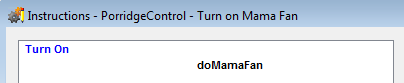

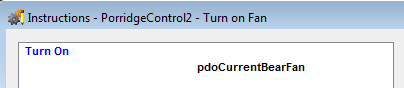

Then the “Turn on Fan” block goes from this command to turn on a particular output:

To this more generic command which will turn on the appropriate output for the current bear:

Ta-da! That’s it! Now that you’ve changed your logic to loop through and do the same monitor/control steps for EACH bear, expanding in the future will be super easy. Just add the I/O points, and initialize them in your pointer table and you’re controlling an even bigger part of the world!

Really?

Ok, this particular example was a bit contrived. I’m sure all you real-world control engineers will have suggestions for more realistic ways to solve similar problems, yes? Let’s hear from you! Questions? Comments? Do share…

-OptoMary